December 25, 2025

2 min read

Add Us On GoogleAdd SciAm

Bizarre Ecosystem Discovered More Than Two Miles beneath Arctic Ocean

Dynamic mounds made of methane at a depth of some 3,640 meters act like “frozen reefs” for a bizarre array of deep-sea creatures, new observations reveal

UiT / Ocean Census / REV Ocean

Deep down in the Arctic Ocean, life becomes bizarre. One might suppose that at its greatest depths, the icy, dark water would be inhospitable to much—but a new discovery reminds us that that is far from the case.

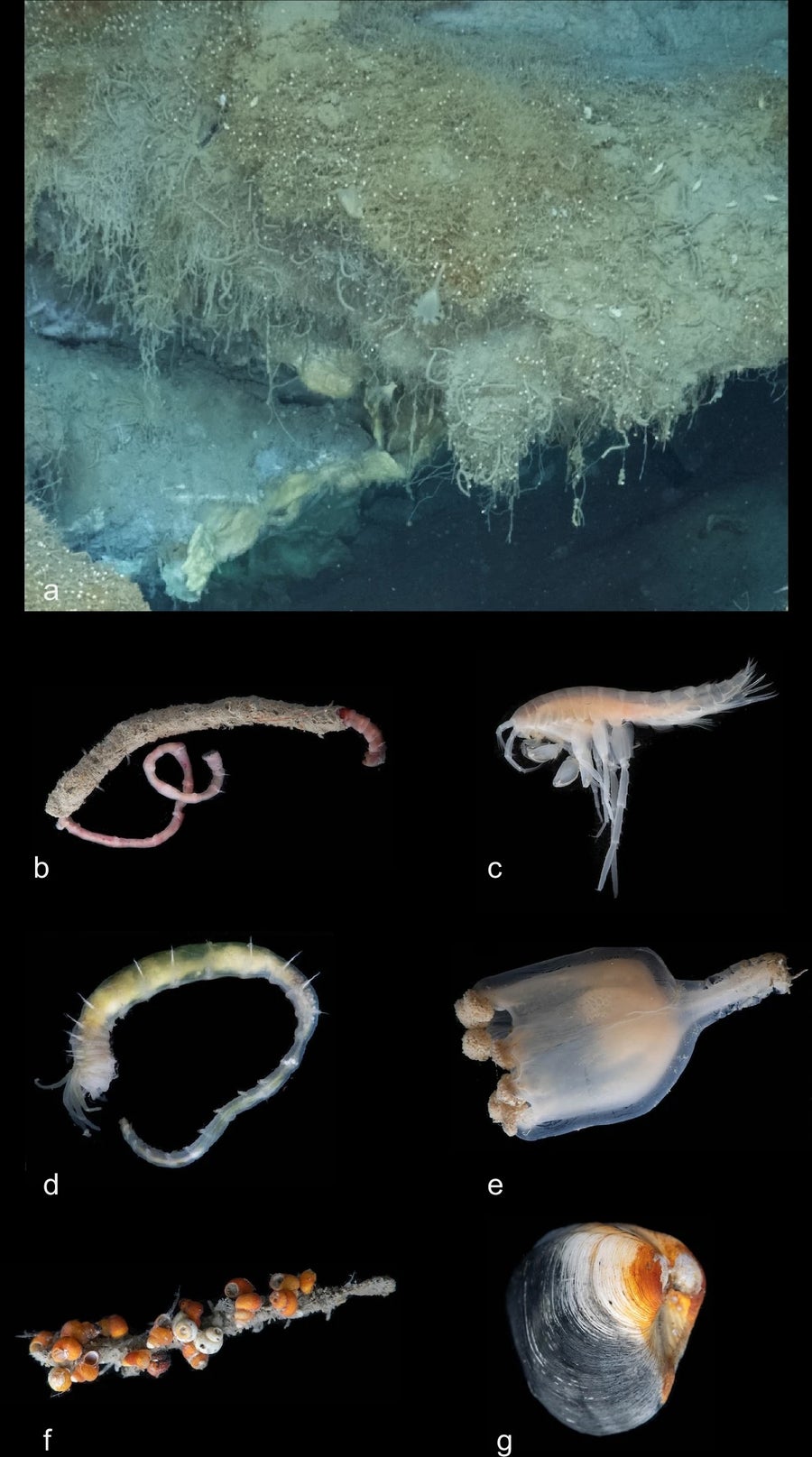

Off the coast of Greenland, the deep seafloor is littered with towering mounds made of crystallized methane and other gases. Known as the Freya hydrate mounds, these structures act like a “frozen reef,” a haven for creatures that have evolved to live in environments unlike any other on Earth.

In a new paper published in Nature Communications, scientists document the deepest ever found of these mounds, at 3,640 meters—or some 2.26 miles—below the surface. The discovery was made as part of the Ocean Census Arctic Deep–EXTREME24 expedition to explore and research the Arctic environment and document ocean life using tools such as underwater robots.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Incredibly, the mounds, which are also known as gas hydrate cold seeps, release methane gas flares some 3,300 meters up into the water—the tallest such flares ever recorded. Over time the mounds collapse and reform, a dynamic process that the researchers say gives insights into the Arctic’s various ecosystems.

UiT / Ocean Census / REV Ocean

“These are not static deposits,” Giuliana Panieri, a study co-author and a professor at the Arctic University of Norway, said in a statement about the new research. “They are living geological features, responding to tectonics, deep heat flow, and environmental change.”

Gathered at the mounds are chemosynthetic creatures—life that has evolved to depend not on sun-powered photosynthesis for food but on chemical reactions instead. Some of the creatures seen at the Freya mounds are also found at hydrothermal vents, or fissures in the seafloor through which hot, chemical-laden water erupts, the researchers said, suggesting these ecosystems may be more intertwined than previously thought.

“The links that we have found between life at this seep and hydrothermal vents in the Arctic indicate that these island-like habitats on the ocean floor will need to be protected from any future impacts of deep-sea mining in the region,” said Jon Copley, a study co-author and a professor at the University of Southampton in England, in the same statement.

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.